You and I have to make our minds up on many things to save time and energy. We accumulate shortcuts for decisions and beliefs to avoid a mental meltdown.

During this intuitive process, confirmation bias lends you a helping hand.

I bet you can answer these without blinking:

- Are cats better than dogs?

- For capital punishment or against it?

- Are men better drivers than women?

Depending on your answers, you are much more likely to notice examples around you that confirm your views. And dismiss what you don’t want to hear.

Chances are also that you have a few arguments ready to fire and back up your choice without doing much thinking, right?

We accumulate ideas about many things: How we think the financial markets will fare. How to fix global warming. And the best way to cook salmon.

What is confirmation bias?

In the first season of Fargo, Lester Nygaard looks at a poster in his basement that reads: “What if you’re right, and they’re wrong?”

Just like Lester, we like to cling on to the thought that we were always right. Alas, confirmation bias can cause people to become overconfident and avoid second-guessing their views.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and remember information in a way that confirms or supports our prior beliefs or values.

Raymond S. Nickerson, psychologist

When English psychologist Peter Wason coined Confirmation Bias in 1960, research suggested that people are biased towards confirming existing beliefs. Later, confirmation bias was defined as people’s penchant to test one-sided hypotheses where our minds focus on a single outcome while ignoring others.

To paraphrase, you and I instinctively select the information that supports our views while overlooking opposing views or contrary information.

Practically, this means that you should expect more confirmation bias when you (or others):

- desire an outcome

- have deeply rooted beliefs

- are emotionally engaged.

Why confirmation bias?

One reason for confirmation bias is the trouble and effort it takes to change one’s mind. It is simply more convenient to stick to your current beliefs.

Another reason is that your mind would probably have a meltdown if you had to challenge your ideas all the time. This inner struggle is known as cognitive dissonance, which is an essential factor when explaining confirmation bias.

Cognitive dissonance is experienced as psychological stress when you carry two conflicting ideas or beliefs simultaneously. In this state, your subconscious mind finds it much easier to manipulate or ignore facts to make things fit.

Your mind is itching to choose sides

Things left undecided are stressful to the mind. Choosing sides restores internal harmony and reduce discomfort.

For example, if you believe that global warming is something made up by those leftists, you tend to favor articles that confirm your view. At the same time, you tend to avoid contradictory information that refuels the fire of cognitive dissonance.

Or, if you have just invested thousands in a hot, but overvalued, stock, your mind will intuitively cherry-pick “evidence” that you made the right decision. If the stock plunges, you can always blame the economy, the vegans, or other people who can’t “grasp” this company’s vision. Ultimately, you are right, and they are wrong. At least that’s what you tell yourself.

What’s the motivation behind confirmation bias?

Besides cognitive dissonance, confirmation bias is hard to avoid because of two conscious sets of desires:

- To be right

- To have been right all along

The first desire is about humanity’s search for truth – the great quest of life. Is there anything better than when you can say, “See, I told you so”?

The 500 dollar question, though, is this:

Are you self-confident enough to look for the truth, even if it doesn’t please your ego? Even if it might cause a little psychological stress when you find contradicting evidence that forces you to change your mind? If yes, hang on to the desire to be right.

That leads us to the second desire, which is less noble. I’m sure you can already picture a stubborn friend who, especially in hindsight, always knew they were right. At least, they seemingly can’t ever be wrong.

Do you know this guy? Then check out: Mount Stupid and the Dunning-Kruger Effect

As the great philosopher Marsellus Wallace in Pulp Fiction said: “That’s pride f***ing with you.” Everyone’s wrong sometimes. Just admit it and get on with everything. Don’t be like the Flat Earth Society and keep reiterating your views when evidence stacks against you.

Oh, speaking of making odd truths …

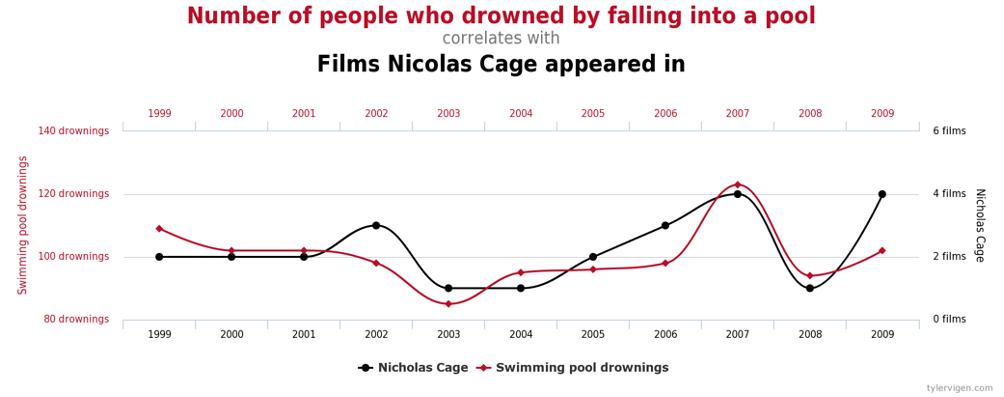

The unusual connection between deaths by drowning and Nicholas Cage movies

Did you know that there’s almost a linear connection between movies starring Nicholas Cage from 1999 to 2009 and deaths by drowning in a pool?

Just look at this graph and see for yourself:

Go ahead and laugh at the ridiculous graph on Nicholas Cage. But remember this: People make other, just as silly, connections in life.

Let’s say you believe that meditation is the key to happiness. You know other people at the yoga club who meditate. They always appear so harmonious. Thus, meditation must be the secret path to happiness, right?

Not really. This type of reasoning is another example of confirmation bias. Your brain’s desire to make simple, apparent connections disregards all other evidence that you did not take into account. Besides, if you wanted to, you could argue the opposite case by finding all the suicidal people who meditate every day.

Statistics and perceptions are easy to manipulate because we:

- don’t check for numerous variables (health, relationship, age, income, mindset, etc.)

- don’t have an adequate sample size (how many examples can you think of?)

- don’t have a representative sample (focusing on members of your yoga class)

The making of these false correlations is usually due to “if this, then that” propositions, which are feeding confirmation bias towards self-made truths.

Confirming outcomes with “if this then that” propositions

If you’re like most people, you make “if this, then that” propositions – small confirmation bias stories that explain outcomes.

Here are a few examples:

- “If I get this job, then I will feel more successful.”

- “If I buy this new car, then everyone will like me.”

- “If I improve my health, then I will be happy.”

I have made a lot of these small wagers. As I write this, I wonder why? First, they feel conveniently simple. Secondly, these inner deceptions can drive goal setting and motivation, which is good.

But here’s the problem: When an outcome either does or doesn’t happen, you are almost guaranteed to attribute the wrong factor.

Let’s say you make this assumption: If I get rich, then I will become happier.

One outcome is that you get rich and feel incredible about yourself. Is this sensation due to the extra cash sitting in your account? Or could it be that your newfound happiness comes from the personal development of new and improved habits, mindset, and self-confidence while you chase your financial goals?

The second outcome is that you get rich but feel unfulfilled. Maybe you win the lottery or inherit a large sum of money. From one day to the other, you go from broke to loaded. Goal achieved! But, after a while, you still feel like crap. Should you blame the piles of money? Of course not. While the money situation changed, you stayed the same.

Beware of these “if this then that” propositions. Not only are they causing confirmation bias, but they will also cause focusing illusion, where the mind attaches too much importance to one factor instead of looking at all available data points.

You’re not going to become happier because of any single factor or outcome. It’s always the sum of the parts and probably much more complicated than you think.

Real-life examples of confirmation bias

We see and think of what we want to believe. The faster you acknowledge this, the faster you will be aware of your own confirmation bias and be able to question your thinking. Today, this seems to be a rare trait and one worth pursuing.

Here are a few examples of confirmation bias gone wild in the real world.

Confirmation bias and information search

Imagine yourself scanning the latest news. You will automatically notice the headlines that confirm your worldview (and nod with approval). Some people even go to the same media to make sure to avoid any cognitive surprises.

Confirmation bias is the mother of all misconceptions. It is the tendency to interpret new information so that it becomes compatible with our existing theories, beliefs, and convictions.

Rolf Dobelli

Headlines that contradict your views are momentarily registered but typically quickly forgotten. However, sometimes you decide to click on one of these contrarian articles to get the water boiling.

Even if presented with new information, your mind tells you to find flaws in the evidence or other ways to disregard the content to remain in the status quo.

Beliefs are often harder to move than a grand piano.

Confirmation bias and politics

Remember the last political debate you watched?

Two candidates with conflicting views on an issue have access to the same facts. Do they ever agree? No, they feel even more validated by the evidence, which enforces their worldview.

Taxes are still too high or too low. Government spending is either too much or too little. No surprises here.

That’s why watching a political debate is mostly a waste of time. Forget about going into a discussion with an open mind. You are most likely just to confirm what you already believed. So are the politicians on your screen.

Confirmation bias and stock investing

Investors are supposed to be rational, number-crunching, cold-hearted people who look at facts and figures, and nothing else.

In reality, investors are just as prone to search for evidence that confirms their positions while dismissing data that questions their investment thesis.

What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact.

Warren Buffett

Brady, a seasoned investor, crunches all the fundamental numbers to reach the rational conclusion that a new tech stock is in terrible financial shape. The company is now off the buy list.

Shortly after, the stock shoots through the roof.

How can it be, Brady thinks to himself? He frantically starts to look for evidence that he was right. When the share price corrects, Brady is confirmed that the stock is “risky” and “overvalued.” But he goes back to point at the holes in the cheese when the share price increases again.

Like Brady, I have missed the boat on many a stock due to confirmation bias.

On the other hand, when stock prices only go north in bull markets, overconfidence can result in a disastrous false sense that nothing can go wrong. So, investors are usually blindsided when the shiitake hits the fan.

The rationale is this:

It’s more important to ask yourself why you could be wrong than why you are right. Force yourself to consider the opposite view, at least from time to time.

Why proof always supports your case

You can go through life and believe that “good things will happen to me” or “bad things will happen to me.” Either way, you will find daily proof to support your case.

We need to establish beliefs about the world, life, career, choices, and everything else.

Our beliefs and knowledge accumulate through experience and study. And this is all we’ve got to make decisions in ambiguous and uncertain situations. Therefore, we will trip into the confirmation bias trap time and again. And that’s human. But it would be best if you still took precautions.

What can you do about confirmation bias?

First off, be aware that confirmation bias exists and acknowledge that you’re not the exception to the rule. Awareness gives you the best chances to hedge from its downsides.

Obviously, you agree with everything in this article. But for other pieces of information you come across, you can do a quick analysis:

- What did you agree with automatically?

- Which parts did you disregard (and did you even realize it)?

- How did you react to the arguments, whether you agreed or disagreed?

If you stand before an important decision, such as a more significant investment, or life-changing choices, you should be a little more thorough:

- Do your sources have skin in the game?

- Is your preferred choice rational or emotional?

- Were you persuaded – or did you think for yourself?

- Did you think it through (all scenarios)?

- Can you point at concrete evidence that backs up your decision?

- Did you search for disconfirming evidence?

It feels counterintuitive to look for evidence that contradicts your belief. But if your decision has more immense consequences, you need different sources and people with the opposite opinions.

It’s not easy to guard against confirmation bias, but as you have just learned, you can protect against its downsides and make better decisions with practice.